Difficulties in the metallographic preparation of cast iron

The main challenge when preparing samples of cast iron is to retain the graphite in its original shape and size to ensure a correct representation of the cast iron’s microstructures.

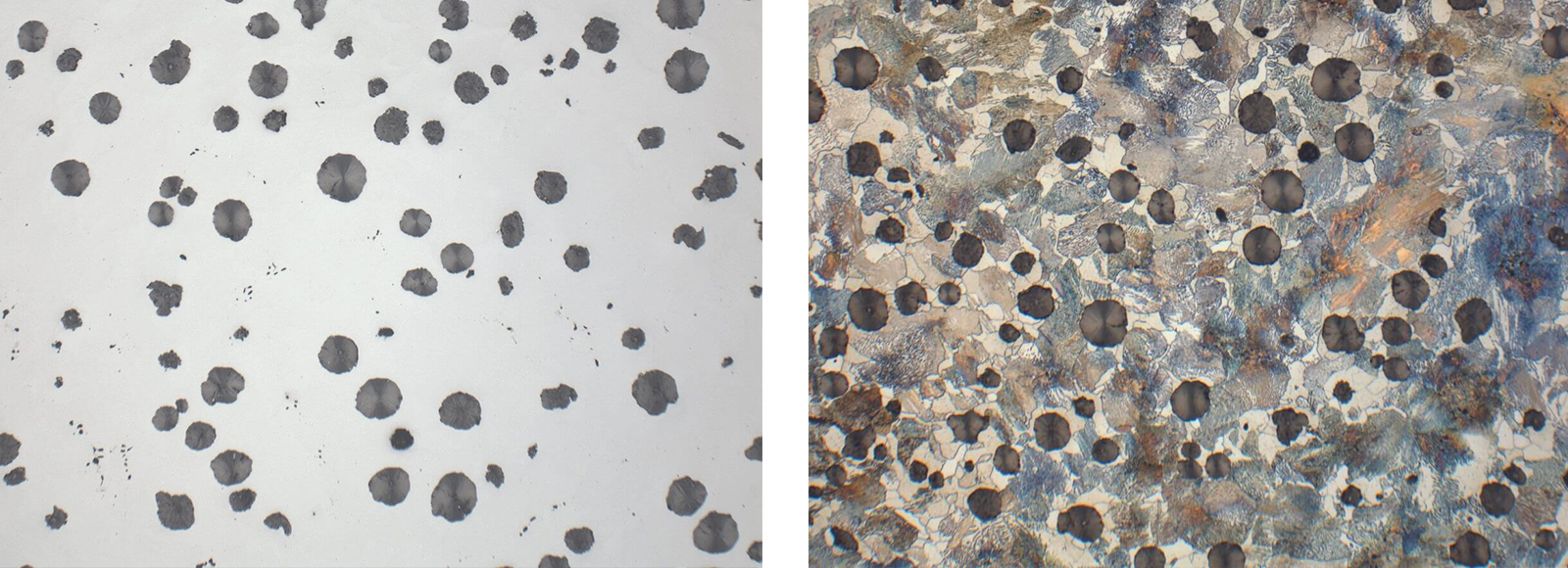

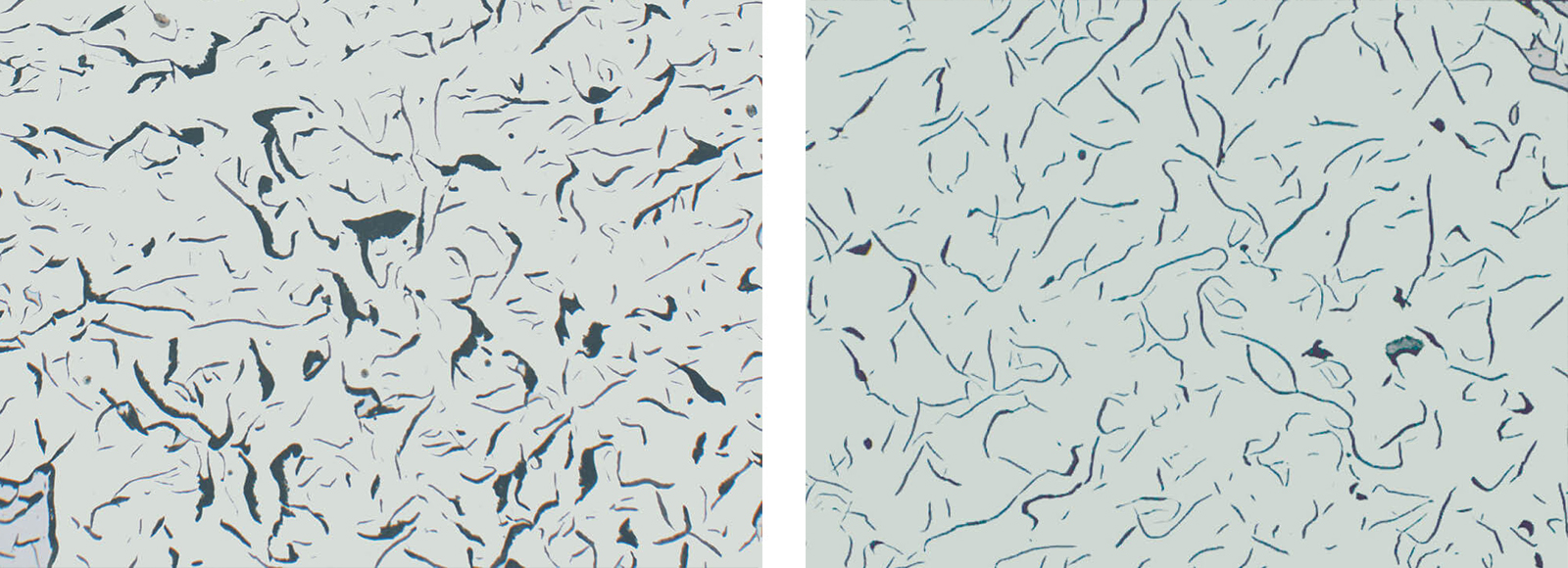

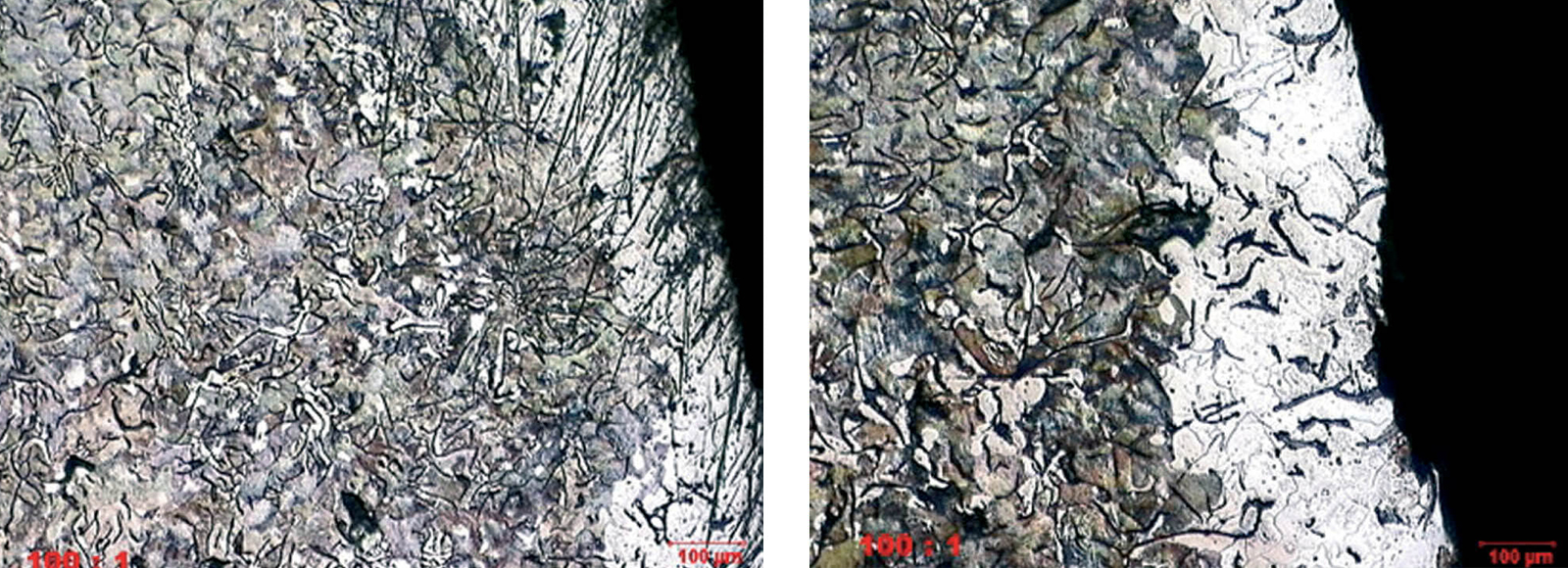

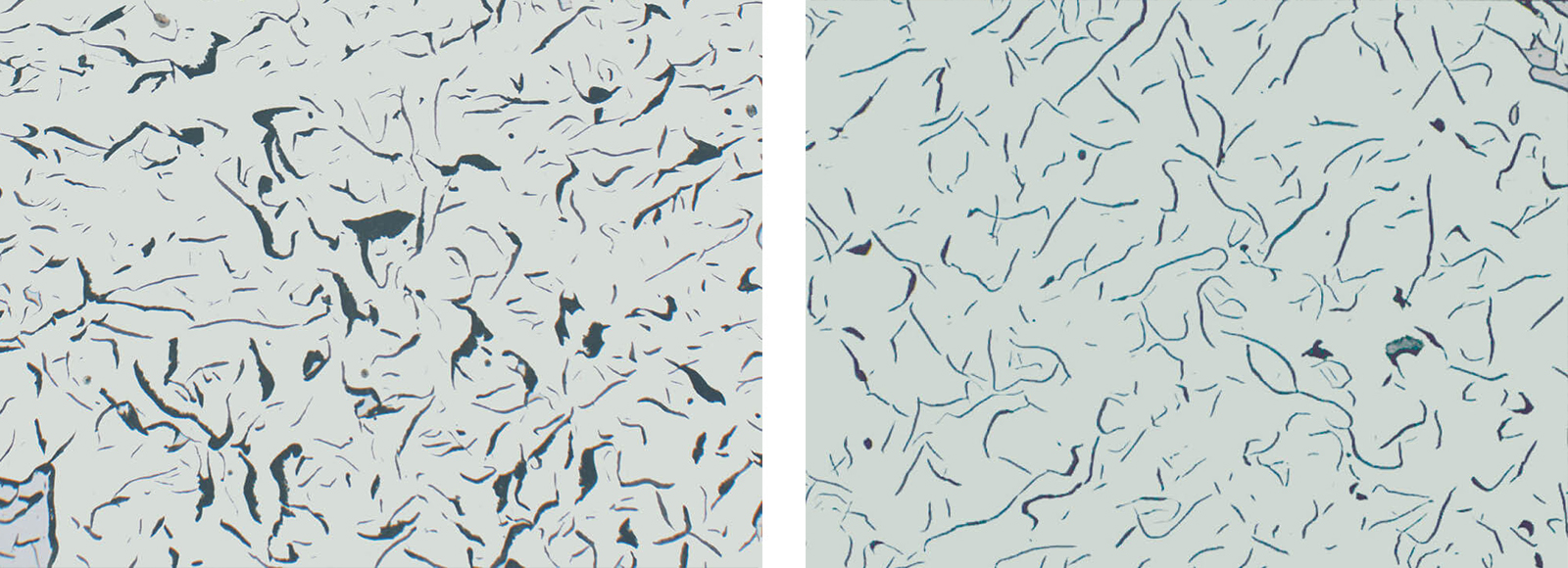

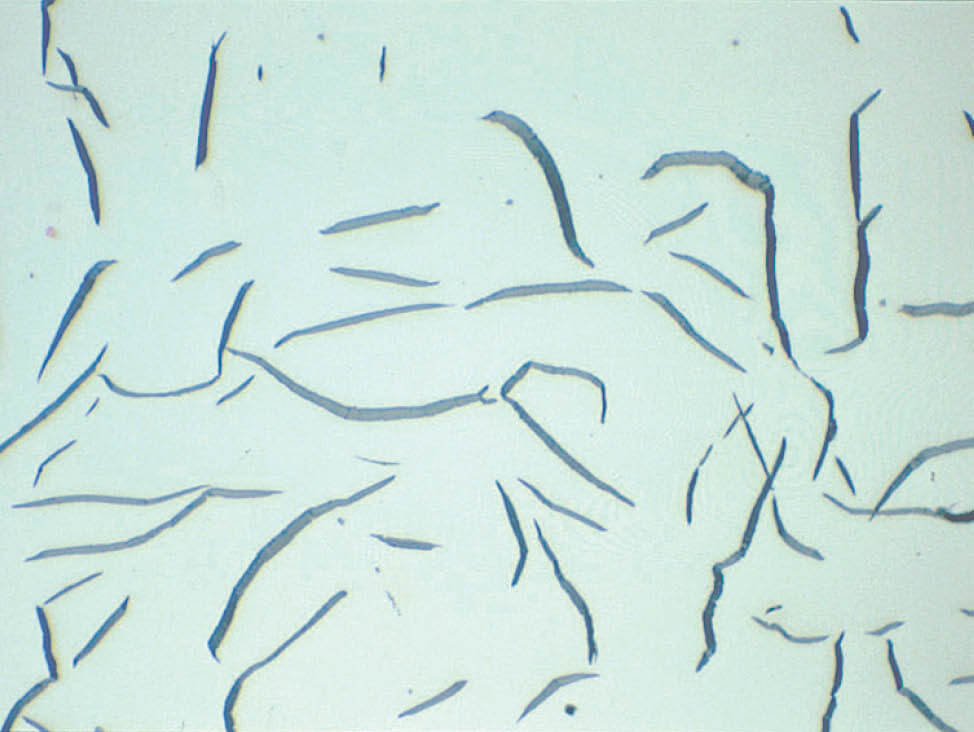

Fig. 4: Grey iron with flake graphite, insufficient polish (Mag: 200x)

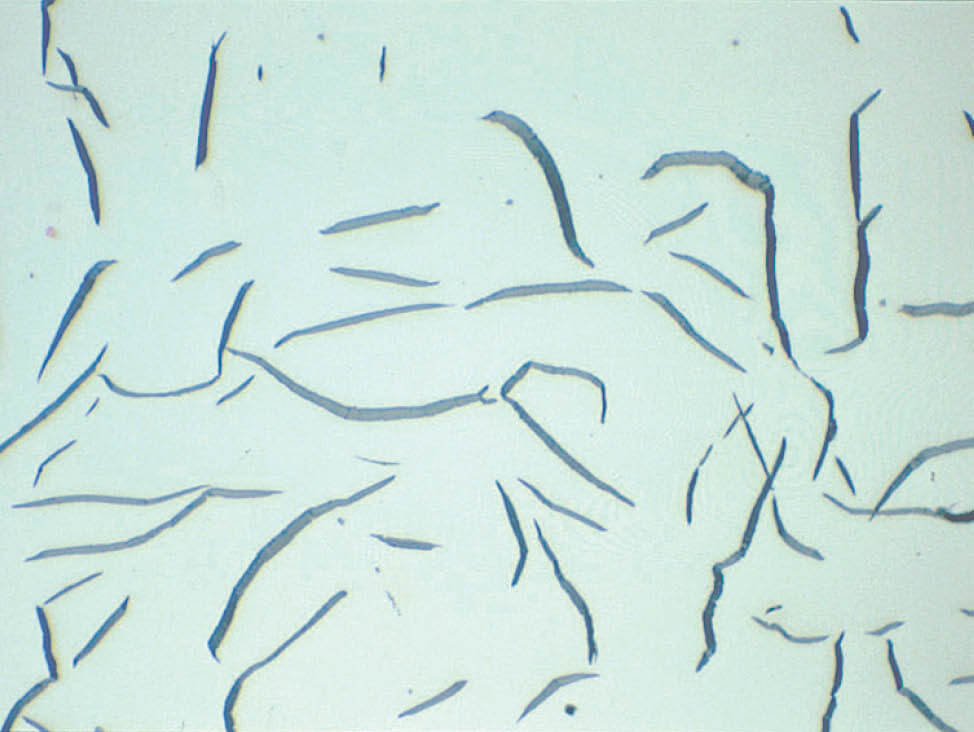

Fig. 5: Grey iron with flake graphite, showing correct polish (Mag: 200x)

In the microscope, the image of the graphite is seen two-dimensionally. However, it is actually three-dimensional. This means that a certain percentage of graphite is cut very shallow during grinding and polishing, with only a weak hold in the matrix. Therefore, there is always a possibility that the graphite cannot be completely retained, especially very large flakes or agglomerations of flakes. As a result, the graphite phase cannot always be retained or polished well.

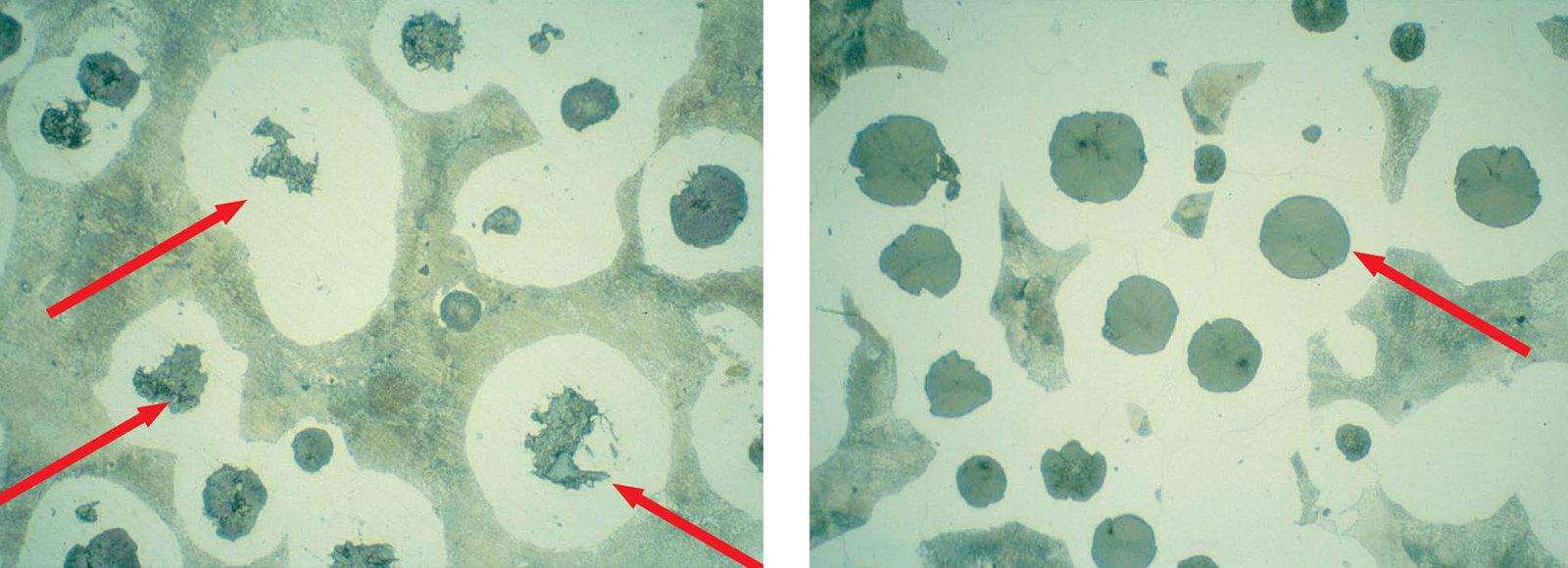

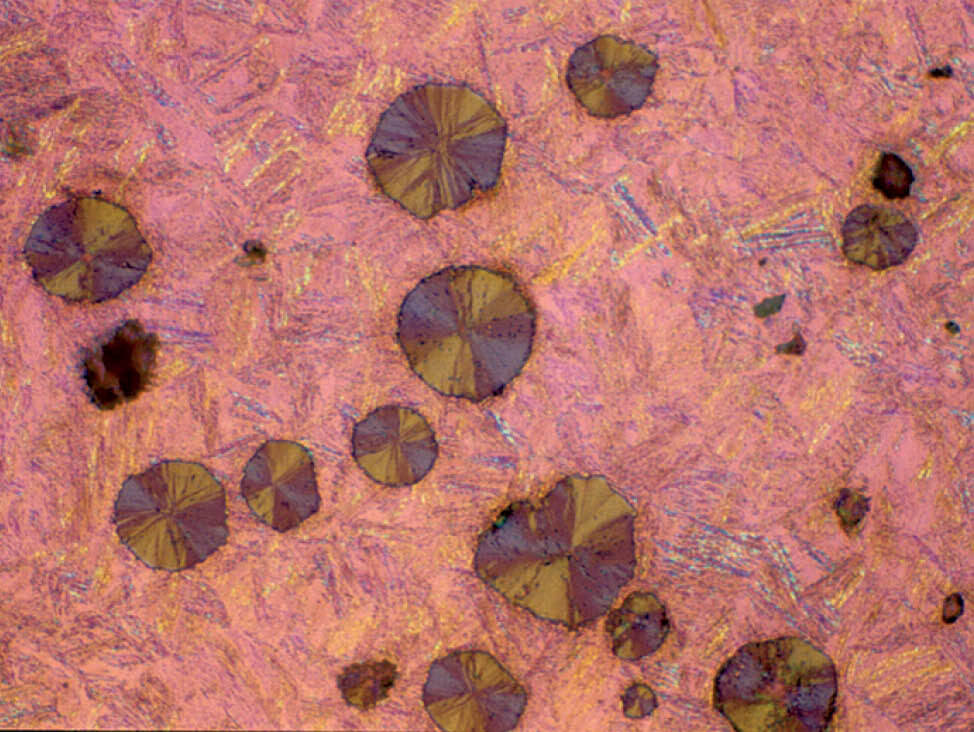

In malleable cast irons, graphite exists in the form of rosettes or temper carbon. This is a friable form of graphite and it can be particularly difficult to retain during metallographic preparation.

A common preparation error is the insufficient removal of smeared matrix metal after grinding, which can obscure the true shape and size of graphite. This is particularly prevalent in ferritic and austenitic cast irons, which are prone to deformation and scratching. For these materials, a thorough diamond and final polish is very important.

Most standard microscopic checks of cast irons are done with a magnification of 100x, which makes the graphite appear black. However, higher magnifications are required to verify if the carbon is completely retained, as well-polished graphite is grey.

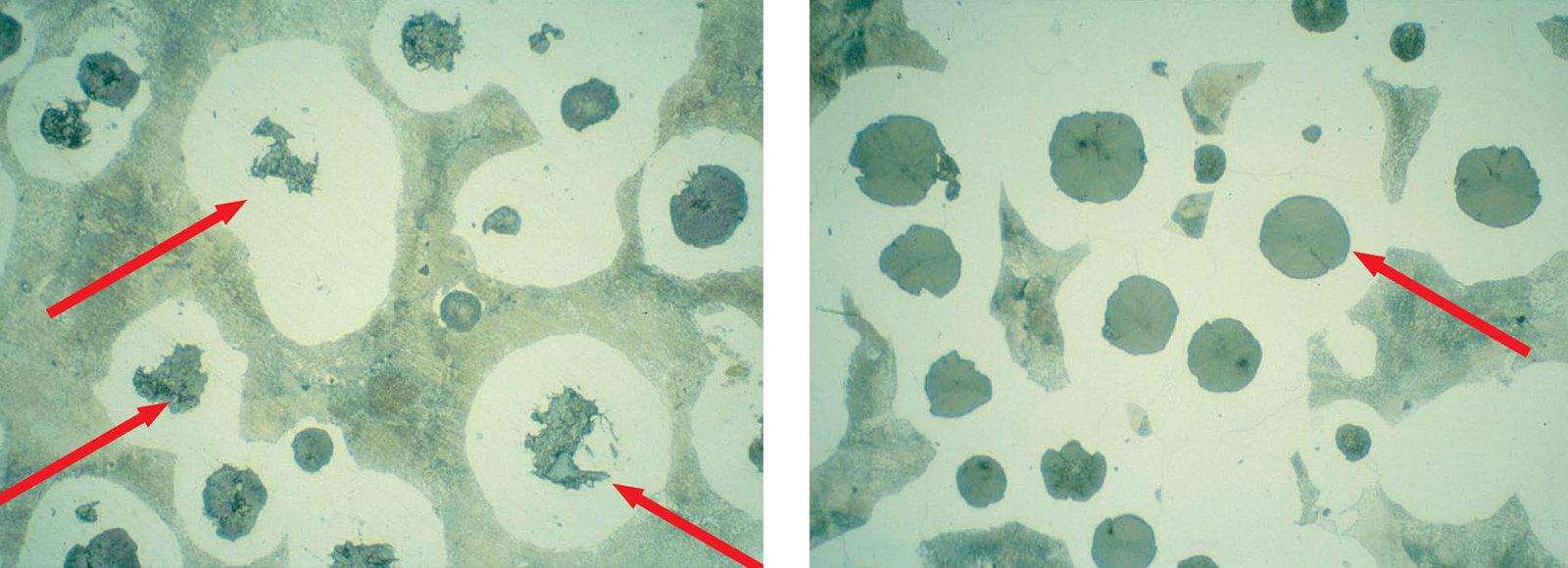

Fig. 6: Insufficient polish leaves graphite nodules covered with smeared metal, etched 3 % Nital (Mag: 200x)

Fig. 7: Correct polish shows shape and size of graphite nodules suitable for evaluation, etched 3 % Nital (Mag: 200x)

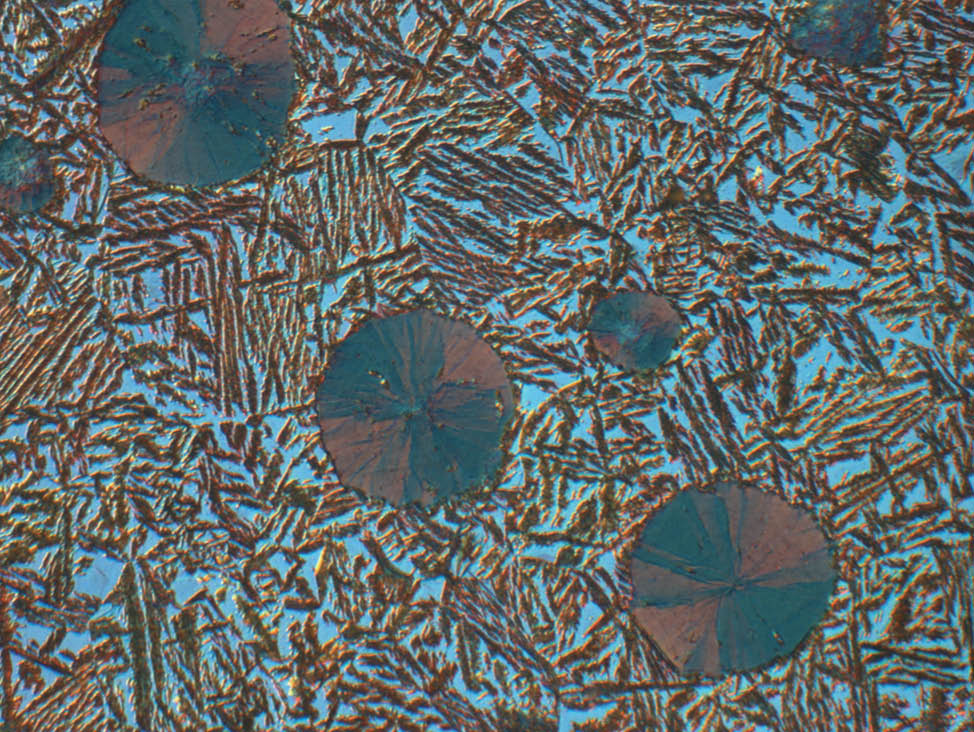

Fig. 8: Well-polished graphite flakes (Mag. 500x)